KakkoKari (仮) Another (data) science blog. By Alessandro Morita

13.8 billion years on a 10.1'' screen

Some moments in one’s life can be awe-inspiring. You know, those moments when you feel deeply connected to something; when things make sense.

Some people would label this feeling as spiritual; not being a very spiritual person myself (at least according to the common definition), I don’t really know how appropriate this attribution is, but I can relate to them. This feeling of connection is reminiscent of something deeper, something important, and that might as well be linked to some higher, unknown entity.

A few moments in my life brought me this kind of awe; for instance, a particular afternoon watching the sunset in Heda, Japan, where I lived while working as an employee at a beautiful hostel:

(sadly, I lost the original photograph - this was taken from my Instagram feed)

(sadly, I lost the original photograph - this was taken from my Instagram feed)

There is another remarkable memory, this time related to Physics, which happened in 2011, when I was 19 years old. This is what I want to talk about today.

“Maybe I should research something”

(picture of my alma mater: the Institute of Physics at the University of São Paulo, Brazil)

(picture of my alma mater: the Institute of Physics at the University of São Paulo, Brazil)

I was in the end of my second year undergrad, and had recently started feeling like I was lagging behind. Most of my friends were doing research projects under a faculty member; some, especially those doing experimental work, had been doing it for almost a year at that point. I had never been in a hurry regarding research work; I knew it would come at some point, and felt like I needed to understand the fundamentals better before diving into some problem. I wouldn’t even know what I liked in the first place if I didn’t take more classes!

Yet, as we entered the second half of our 4-year course, I felt like I should start looking for a research topic, too. After a few months talking to professors on a variety of topics – Astronomy, Mathematical physics, Computational physics – I ended up working in Cosmology with a young assistant professor who had just joined USP’s Physics department after his post-doc.

My first task was to learn enough General Relativity to understand the textbook we would be working with: Scott Dodelson’s Modern Cosmology, a standard reference in the field. The goal was to understand how we model the expansion of spacetime, from the Big Bang until now; first, within a simplified framework of a Universe that appears the same anywhere you are and anywhere you look at, then moving onto a more complex description of the Universe where we allow fluctuations of density, energy and temperature to take place.

The initial simplified framework has a fancy name: the smooth Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker metric. Simply put, it describes the universe as an expanding space, starting from zero size in the beginning; the only free parameter is the so-called scale factor, usually writen as $a(t)$, which can be interpreted as the radius of the Universe at time $t$. We usually set $a = 0$ at the Big Bang and $a = 1$ today.

If we can find $a(t)$, we can find the large-scale dynamics of spacetime for any cosmic time $t$.

It so happens that the dynamics of $a$ can be found via the Einstein field equations of General Relativity, a set of equations that I, an aspiring physicist, had known how to write long before I knew what they really meant:

\[G_{ab} + \Lambda g_{ab} = \frac{8 \pi G}{c^4} T_{ab}\]I won’t dwell into the details of what each term means – the left-hand side refers to the curvature of space-time; the right-hand side corresponds the matter, energy and pressure present in it.

On a side note, I remember when I first saw this equation: it felt magical how Newton’s gravitational constant $G$, the speed of light $c$, and the number $\pi$ were all in the same expression.

Plugging the FRW ansatz into the Einstein equations yields the so-called Friedmann equations (where we set $c=1$, as most physicists do, for simplicity):

\[\left(\frac{\dot a}{a}\right)^2 = \frac{8\pi G}{3} \rho + \frac{\Lambda}{3}\] \[\frac{\ddot a}{a} + \frac{4\pi G}{3} (\rho + 3p) = \frac{\Lambda}{3}.\]Here, $\rho$ and $p$ denote the energy density and pressure of the matter in the Universe, respectively, and $\Lambda$ is related to dark energy. These differential equations are the mechanism by which we can relate “stuff” in the Universe with how fast it grows – we need to encode their dynamics into $\rho$ and $p$, and solve for $a(t)$.

The age of the Universe

Now, there is a lot of stuff in the Universe – regular matter (so-called baryonic), dark matter, dark energy, light, neutrinos, and so on, each with their own complicated dynamics which take Physics students years to understand.

It turns out we can mix it all together into the Friedmann equations in order to obtain a single differential equation for the time-evolution of the scale factor, which can be then integrated. More precisely, we can write

\[\left(\frac{\dot a}{a}\right)^2 = H_0^2 \left( \frac{\Omega_\mathrm{baryons} + \Omega_\mathrm{dark\;matter}}{a^3} + \frac{\Omega_\mathrm{radiation}}{a^4} + \frac{\Omega_\mathrm{curvature}}{a^2} + \Omega_\mathrm{dark\;energy}\right)\]where several new parameters have appeared, and it is worth that we explain what they are:

- $H_0$ is the so-called Hubble parameter: it measures how fast distant galaxies seem to be receding away from us, in the context of Hubble’s law;

- The $\Omega$’s are dimensionless parameters relating to the energy contribution of each component. For example, $\Omega_\mathrm{baryons} \sim 4.86\%$ means that about 4.86 percent of the energy of the Universe comes from regular (baryonic) matter.

In practice, we can combine dark matter and baryonic matter into a single parameter, and ignore that of radiation which is much smaller than the others. We do this below.

All these parameters can be inferred from complex cosmological and astronomical observations, such as the Planck mission launched in 2009.

For me, at that time, the important thing was not how they were obtained, but the fact that, with some algebraic manipulation, the equation above could be brought into one where one could explicitly calculate the age of the Universe! It would suffice to isolate time as a function of the scale factor, and integrate between the Big Bang and now.

Now, this wasn’t explicitly part of my research, but I felt like I had to do it. It just seemed like such an exciting thing to do, and not too complex – differential equation solvers are available even in Excel.

First, I had to write the equation for the age of the Universe, $t$, explicitly:

\[t = \frac{1}{H_0} \int_0^1 \frac{da}{a \sqrt{\displaystyle \Omega_\mathrm{matter} a^{-3} + \Omega_\mathrm{dark\;energy} + \Omega_\mathrm{curvature} a^{-2}}}.\]It isn’t hard to show mathematically that the integral is less than 1, so the age of the Universe is approximately $1/H_0$, with a correction given by the integral. To solve this integration requires numerical calculations, so I had to resort my limited programming skills.

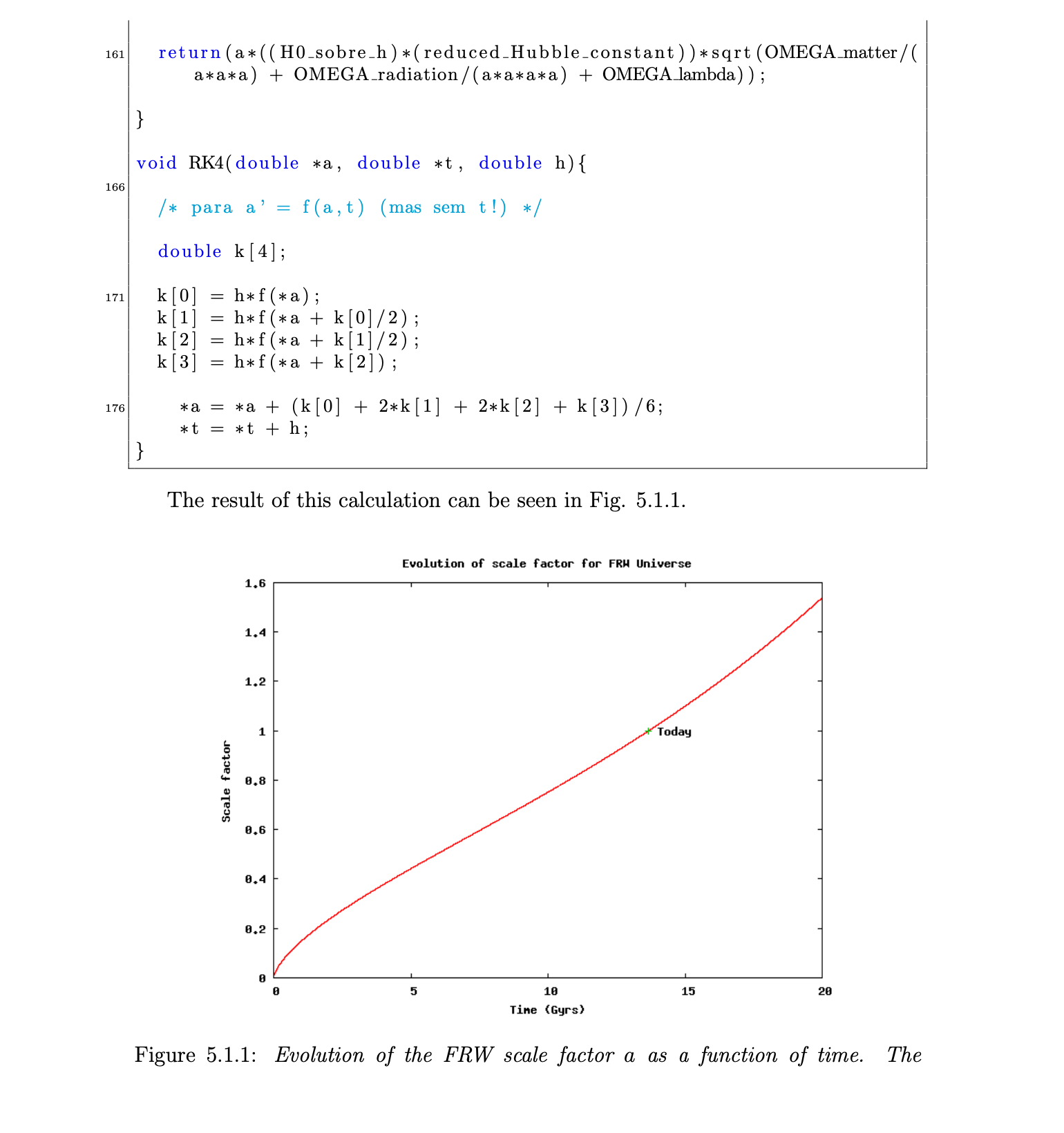

So, with the 2-semester experience I had in programming (which I had learned in C – perhaps the most ill-suited language for quick-and-dirty scripting of scientific code), I wrote a whooping 178-lines-long C code to read cosmological data and integrate the Friedmann equation via Runge-Kutta; see below for a screenshot of a report I wrote on this event.

The answer I got: 13.8 billion years.

That was my awe-inspiring, spiritual-ish moment. I had seen and read this number many times – it was in the first popular book I read about Physics, in documentaries, and, if rounded up, even in the opening song for The Big Bang Theory. I would not have expected to be able to calculate such a number by the end of my second year undergrad; and, in hindsight, I only did it because I severely glossed over many details, like how the cosmological parameters ($H_0, \Omega_\mathrm{matter}$ and so on) are inferred from observational data in the first place.

Nonetheless, I keep that moment in mind as a very happy memory: I was 19 years old, lanky and ignorant of so much, yet I was able to compute the age of the Universe we live in on my trusty 10.1’ Acer netbook. I felt inspired to learn more about Cosmology and gravity, and that is what I did over the following years studying Physics.

Appendix: reproducing the calculation

For the sake of completeness, I will write down a much shorter script in Python which does essentially the same thing. We ignore radiation and use the values for the cosmological parameters reported in this paper, which are read off the Planck collaboration 2016 report: we calculate

\[t = \frac{1}{H_0}\int_0^1 \frac{da}{a \sqrt{ \Omega_m a^{-3} + \Omega_\Lambda + \Omega_k a^{-2}}}\]where $\Omega_m$ is the combined baryon and dark matter contribution, $\Omega_\Lambda$ corresponds to dark energy, and $\Omega_k = 1 - \Omega_m -\Omega_\Lambda$ is the “curvature” contribution.

import numpy as np

from scipy.integrate import quad

# cosmological parameters following https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-4357/aafb30/pdf

omega_matter = 0.308

omega_lambda = 0.6911

omega_k = 1 - omega_matter - omega_lambda

H0 = 67.8 # ±0.9, units of km per second per megaparsec

We also need to convert $H_0$ (which, technically speaking, has units of 1/time) to a proper unit, which we will choose as billions of years:

- $H_0 \mbox{ has units of } \mathrm{km \, seconds^{-1} \, Mpc^{-1}}$;

- $1 \; \mathrm{Mpc} = 3.086 \times 10^{19} \; \mathrm{km}$, and;

- $1 \; \mathrm{year} = 31536000 \; \mathrm{seconds}$

# Calculate 1/H0 in units of Gyr (i.e. billion years)

inverse_hubble = 1/(H0/(3.086e19) * 31536000) / 10**9

print(round(inverse_hubble,2), "billion years")

>>> 14.43 billion years

We can now explicitly compute the integral and multiply by $1/H_0$ to get the age of the Universe:

integral = quad(lambda a: 1/(a * np.sqrt(

(omega_matter)/a**3 + omega_lambda + omega_k/a**2 )),

0,1)[0]

age = integral * inverse_hubble

print(round(age, 2), , "billion years")

>>> 13.81 billion years

If you like analytical results, we can do that too if we consider a Universe with only matter and a cosmological constant; this means we will exclude radiation (which affects the integral only slightly) and the curvature term.

As Wolfram Alpha can us calculate, with $\Omega_m + \Omega_\Lambda = 1$,

\[\begin{align*} t &= \frac{1}{H_0}\int_0^1 \frac{da}{a\sqrt{\Omega_m a^{-3} + \Omega_\Lambda}} \\ &=\frac{2}{3H_0} \frac{ \mathrm{arctanh} \sqrt{\Omega_\Lambda}}{\sqrt{\Omega_\Lambda}} \end{align*}\]which yields $t = 13.80$ billion years using $\Omega_\Lambda = 0.6911$ as before.

Indeed, a similar calculation actually gives us the explicit scale factor:

\[a(t) = \left[\frac{\sinh(3 H_0 t \sqrt{\Omega_\Lambda}/2)}{\sqrt{\Omega_\Lambda/\Omega_m}} \right]^{2/3}\]For those who find themselves interested in Cosmology, a great place to start is Leonard Susskind’s introductory lectures in Cosmology or Barbara Ryden’s book.

Written on August 4th, 2023 by Alessandro Morita