KakkoKari (仮) Another (data) science blog. By Alessandro Morita

Infinite children? A nice problem in probability theory

Consider the following problem:

A couple decides to have a male child no matter what. If their first child is a son, they stop; if it is a daughter, they continue having more children. There is no upper limit on how many daughters they can have before having a son. What is the average number of sons and daughters they will have?

I was once asked this question during a job interview. My solution at the time was intuitive, but it lacked mathematical rigor. In this post, I present you with three solutions, to various degrees of mathematical refinement.

To fix notation: let $p$ be the probability of having a daughter, and $q=1-p$ that of having a son. In the original interview $p=q=1/2$, but keeping things general allows for (1) more concise equations (2) less likelihood of two answers agreeing by coincidence.

1. The brute force approach

One part of the question is actually easy to answer: how many boys will the family have in the end. The answer is 1, with probability 100% - since the couple will not stop until having a boy, and won’t have another son once they have the first, they are guaranteed to have one and only one boy. The expected number of sons is then 1, and we can focus on finding the number of daughters next.

A logical way to get started is to write down the probabilities of the couple having $n$ children, as follows:

- 1 child (0 daughters): probability $q$ (just have a son and stop)

- 2 children (1 daughter): probability $pq$ (have a daughter and then have a son)

- 3 children (2 daughters): probability $p^2 q$ (have two daughters and then have a son)

- …

One sees that

\[\mathbb P(k\text{ children})=p^{k-1} q\]or, in terms of the number of daughters,

\[\mathbb P(k \text{ daughters})=p^kq\]Therefore, the expected number of daughters will be

\[\mathbb E[\text{daughters}]=\sum_{k=0}^\infty k p^kq\]The sum without the $q=1-p$ factor is found to be

\[\sum_{k=0}^\infty kp^k=\frac{p}{(1-p)^2}\]which can be derived by:

- Using basic calculus and the expression for the sum of a geometric series

- Massaging the expression until you find yourself a geometric series

Approach (2) is actually equivalent to the second approach we discuss in the next chapter, so we omit it for now. We will then write approach (1) here for completeness; it is a very common technique for summing a series.

Rewrite the sum (which, by the way, can start from $k=1$ with no loss of generality) as

\[\sum_{k=1}^\infty kp^k=p\sum_{k=1}^\infty kp^{k-1}=p \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{d}{dp}(p^k)\]where we used the common formula $(x^k)’ = k x^{k-1}$ from ordinary calculus. Taking the derivative out (hoping that the series converges), we have

\[\sum_{k=1}^\infty kp^k=p \frac{d}{dp} \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^k=p \frac{d}{dp} \left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right)\]where we used the formula for the sum of a geometric series with starting term $p$ and ratio $p$. Taking the derivative gives

\[\sum_{k=1}^\infty kp^k=p \frac{1-p+p}{(1-p)^2}=\frac{p}{(1-p)^2}\]as claimed. Therefore,

\[\mathbb E[\text{daughters}]=q\sum_{k=0}^\infty k p^k=(1-p) \frac{p}{(1-p)^2}\]or

\[\boxed{\mathbb E[\text{daughters}]=\frac{p}{1-p}}\]For the total number of children,

\[\boxed{\mathbb E[\text{children}]=1 + \frac{p}{1-p} = \frac{1}{1-p}}\]With $p=1/2$, we get the result

\[\mathbb E[\text{daughters}]=1\quad (p=1/2)\]and the total number of children is 2: one son, one daughter.

2. The intuitive (recursive) approach

As correct as the result above is, I always found it lacking; it is purely computational and doesn’t provide a lot of intuition for what is going on. The approach I used during the actual interview was different:

Let $n$ be the expected total number of children. I first wrote:

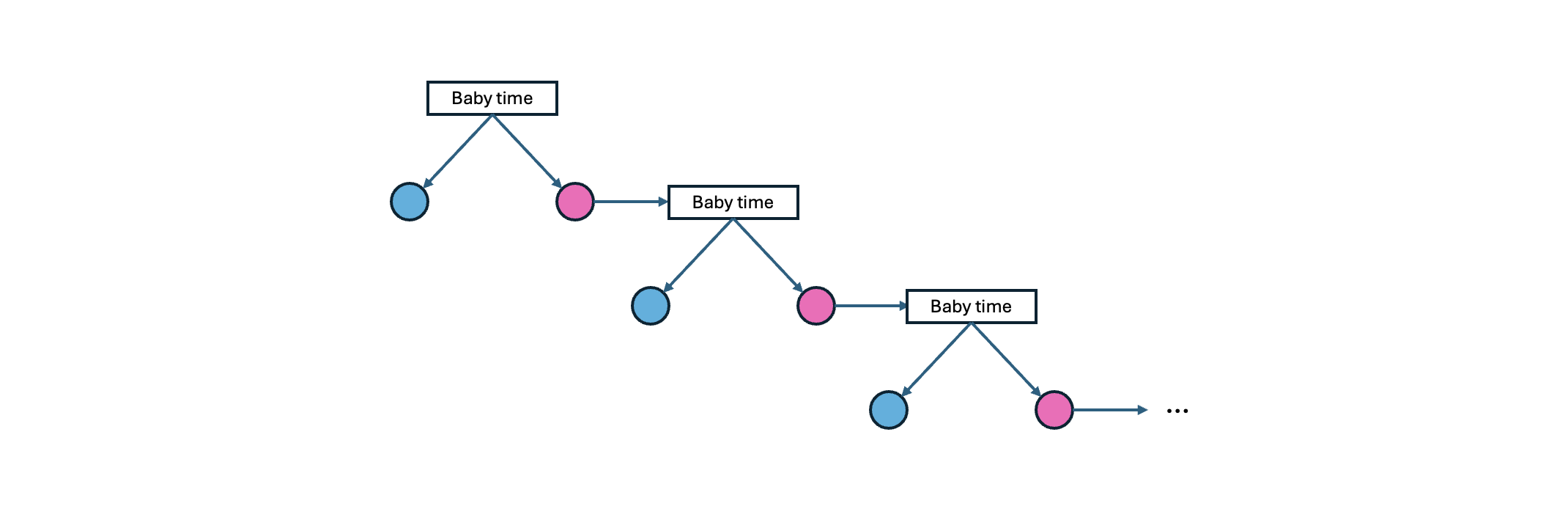

- With probability $q$, the couple has a son (and stops);

- With probability $p$, the couple has a daughter and then needs to start having children again.

Now, “start having children again” felt like somewhat going back to the beginning: aside from the fact the couple now had one child, they had “reset” and would be starting again. We could illustrate the process as something like this (with blue denoting a son, and pink denoting a daughter):

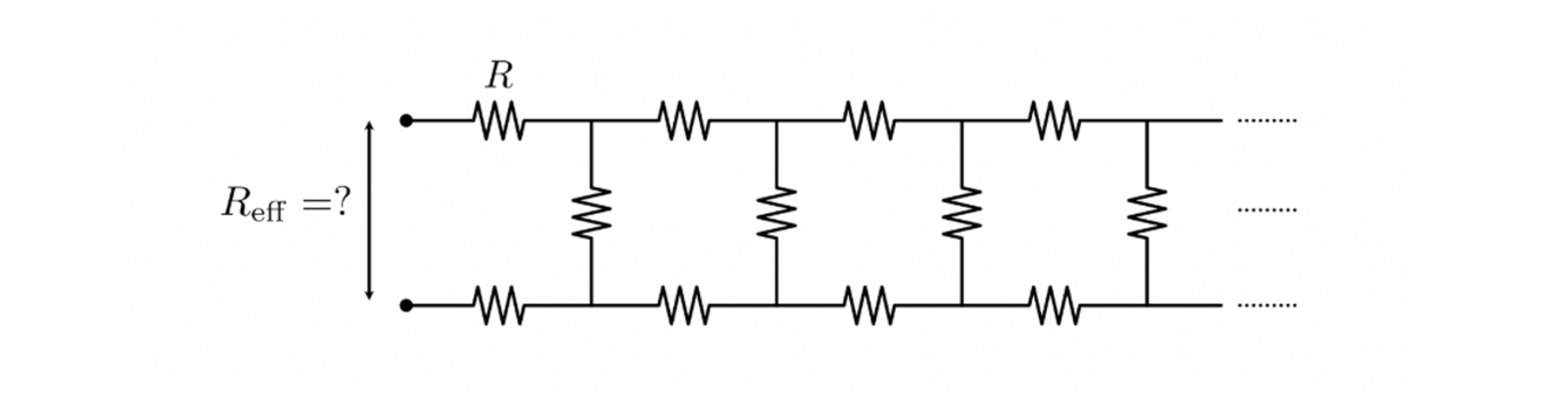

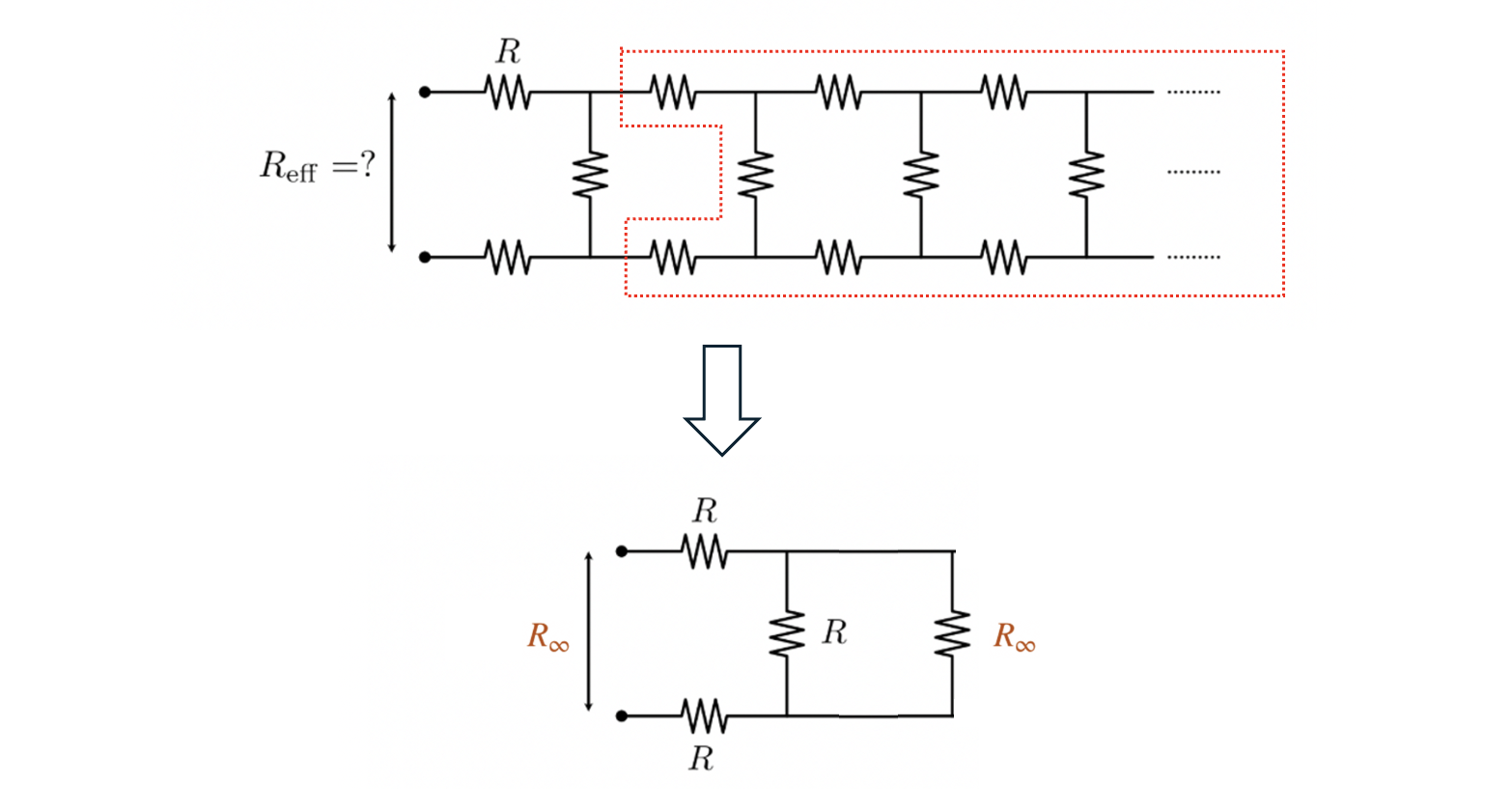

This self-repeating, potentially infinite structure reminded of a class of problems that sometimes appears in university entry exames for engineering schools, namely that of a circuit consisting of an infinite number resistors: one is given a network of resistors, each with resistance $R$, and is required to find the equivalent resistance:

(image from this page)

We learn how to calculate equivalent resistances for circuits in parallel or in series, but since this is infinite, at first it seems impossible to compute.

The trick for solving this type of problem is to realize that we can find a portion of the system that is self-similar, namely the region circled in red is exactly equivalent to the whole system of resistors:

This is only possible since the number of resistors is infinite - were it finite, there would not be an exact match between the part circled in red and the total circuit.

This realization allows us to write a consistency condition for the equivalent resistance $R_\infty$ by using standard rules for serial / parallel resistors:

\[R_\infty = 2R + \frac{1}{1/R + 1/R\infty}\]with solution $R_\infty = R(1 + \sqrt{3})$.

My idea was to do something similar for our babies problem: using the notion that the system “resets” after the first daughter, I could write the recursive relation

\[n = \begin{cases}1 & \text{with probability } q \\ \\ 1+n & \text{with probability } p\end{cases}\]That is: with probability $q$ we have a son and stop; with probability $p$, we have a daughter and start again the process of having children. $n$, our unknown, appears in both sides.

We can then write

\[n = 1\times q + (1+n)\times p\tag{*}\]or

\[n = \frac{1}{1-p}.\]Notice that this is just a rewriting of

\[n = 1 + \frac{p}{1-p}\]i.e. the fact that we get 1 son and $p/(1-p)$ daughters, as we proved before. It works!

We now tackle the reason why I mentioned that this self-repeating business is actually a means to calculate the infinite sum we saw before, namely

\[\mathbb E[\text{daughters}]=\sum_{k=0}^\infty k p^kq\]Let us show this now. We will start from this sum, break it down, and identify a copy of itself inside of it.

First, rewrite the identity $(*)$ as

\[np = n-1\]We will prove that, by using that $n$ is the number of boys (1) + the number of daughters derived from the previous section,

\[n = 1 + (1-p)\sum_{k=1}^\infty kp^k\]then this identity, $np = n-1$, is satisfied; we won’t need any calculus for this, and just the geometric series alone will be sufficient.

Multiplying the expression above by $p$ we get

\[\begin{align*} np &= p + (1-p) \sum_{k=1}^\infty k p^{k+1}\\ &=p + (1-p) \sum_{k=1}^\infty (k+1)p^{k+1} - (1-p)\sum_{k=1}^\infty p^{k+1} \quad\text{(add and subtract)}\\ &=p + (1-p) \sum_{l=2}^\infty l p^l - p(1-p) \sum_{k=1}^\infty p^k\quad \text{(rename index)}\\ &=p+(1-p)\left[\sum_{l=1}^\infty lp^l-p \right] -p (1-p) \frac{p}{1-p}\quad\text{(sum series)}\\ &=p+(1-p)\sum_{l=1}^\infty lp^l-p(1-p)-p^2\\ &=p+(n-1) - p(1-p)-p^2\quad\text{(identify $n$ again)}\\ &=n-1 \end{align*}\]and we have our proof. Essentially, we were able to compute $n$ indirectly by finding it inside its own expression, multiplied by $p$.

3. The Markov chain approach

The third (and, in my opinion, most elegant) approach uses Markov chains.

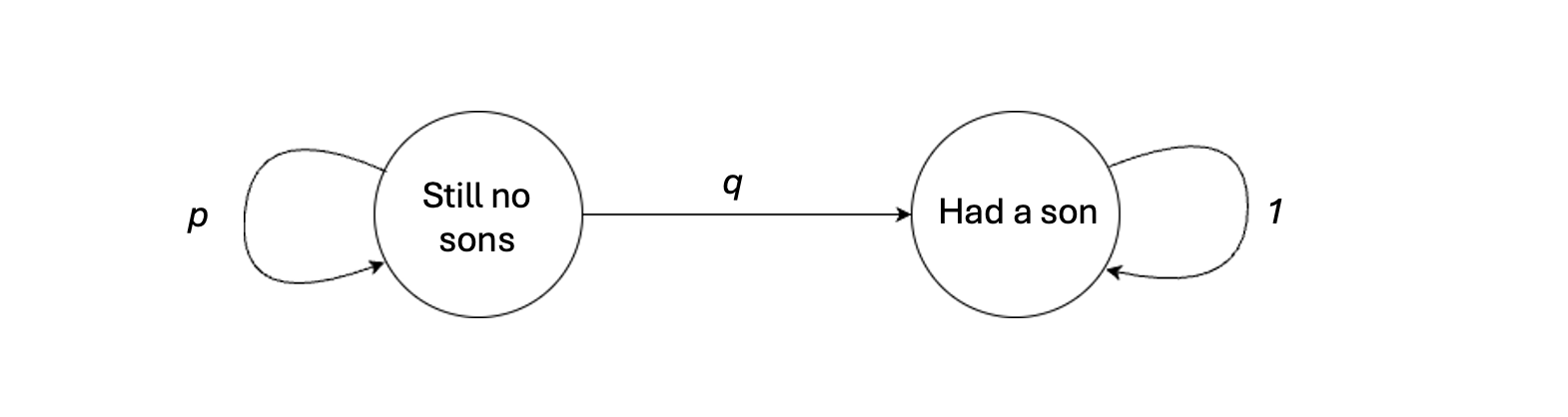

It considers that there are two states in the world: one where we had a son, and one where we still haven’t:

The “had a son” state is, in Markov chain lingo, an absorbing state: once we get there, we never leave (the probability of staying in it is 1). On the other hand, the “still no sons” state is transient: with probability $p$ we stay in it, but with probability $q=1-p$ we migrate to the absorbing state.

This is the classic example of an absorbing Markov chain: there is one absorbing state and one transient state. Let’s dive a bit into the theory.

Recall that in (finite) Markov state theory we denote the probability of transitioning between an initial state $i$ and a final state $j$ as $p_{ij}$, the collection of which can be represented as a transition matrix $P$. $P$ represents the probabilities of going from one state to another in a single step. Analogously, for any power $P^n$, the matrix element $ij$ can be interpreted as the probability of going from $i$ to $j$ in exactly $n$ steps.

In our case, the transition matrix is very simple and given by

\[P = \begin{pmatrix}p & q \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix} \mathbb P(\text{still no sons | still no sons}) & \mathbb P(\text{had a son|still no sons})\\ \mathbb P(\text{still no sons | had a son}) & \mathbb P(\text{had a son | had a son}) \end{pmatrix}\]In general, for a more complex system with $T$ transient states and $A$ absorbing states, $P$ takes a block-wise form

\[P=\begin{pmatrix} Q & R \\ \boldsymbol 0 & \boldsymbol 1 \end{pmatrix}\]where $Q$ is $T\times T$ matrix of transition probabilities among transient states and $R$ is a $T \times A$ matrix of transition probabilities from transient to absorbing states.

As we mentioned above, taking powers of $P$ measures how likely it is to go from a state $i$ to a state $j$ in $n$ steps. We may consider, then, how likely it is to go from a state to another at any number of steps - this gives rise to the Markov chain’s fundamental matrix:

\[N[P] = \sum_{k=0}^\infty Q^k=(\boldsymbol 1-Q)^{-1}\]where the second equality is equivalent to the geometric series for scalars. Notice that only the $Q$ submatrix appears here! The fundamental matrix is key to measuring how many times we will visit transient states before eventually being absorbed.

For our problem, $Q$ is just the 1x1 submatrix $(p)$, hence $N$ is just a number given by

\[N = \frac{1}{1-p}\]There is only one transient state, that of still not having a son; this means that we will visit this state $1/(1-p)$ times. We are done: this is the number of children we have before we stop.

Takeaways

Even though you can have, in principle, an infinite number of children, do not worry - you’re most likely to only have a boy and a girl :)

Happy holidays and a happy 2025!

Written on December 26th, 2024 by Alessandro Morita